One of the key fortresses comprising the Castles and Town Walls of King Edward I in Wales, Castle Beaumaris (or Beaumaris Castle) in Beaumaris, on the island of Anglesey, North Wales, features centuries of British history and, much to the pleasure of architects and historians, remains standing to this day.

Described by one historian as the “most perfect example of symmetrical concentric [design and] planning”, and deemed “the finest example of late 13th century and early 14th century military architecture in Europe” by UNSECO, Beaumaris Castle has been regarded as the pinnacle of English military engineering throughout the reign of King Edward I, whose association with the structure (not to mention many other Welsh castles) is closely tied.

To truly understand the history of Beaumaris Castle, one must learn the circumstances surrounding its construction––and to do so, one must also understand the state of the two combating regions that birthed the structure itself.

Edward I

Since 1070, the Welsh princes had been feuding with the kings of England for control of North Wales––and these hostilities has resurfaced during the 13th century. In 1282, Edward gathered an army and led a bloody insurrection into the neighbouring land, invading the area with the intent to colonise, which included dividing the nation into shires and counties (as it was in England).

Edward, working alongside his royal architect James of St. George, took advantage of the Welsh landscape to dot the northern area’s hills and valleys with multiple castles, creating reinforced towns in which English immigrants could settle. For one such location he set his sights on the particularly populous village of Llanfaes, on the Isle of Anglesey.

By the time Beaumaris was set to take form, there was already construction taking place on multiple strongholds and defensive sites, including at Harlech, Conwy and Caernarfon. The final jewel in the crown of what would become the network of Castles of King Edward I in Gwynedd ––the castle to end all castles––Beaumaris, was nearing realisation.

James of St. George

Little is known about the life and times of Edward I’s master builder, other than the lasting structures bearing his name. Considered to be one of the master architects of the European Middle Ages, his association with Beaumaris Castle and Edward I in Wales remain his most celebrated achievements

The son of a master mason from Savoy, the cultural region in the Western Alps (today, the Savoy region is broadly divided by the French-Italian border), he learned the craft and became a respected designer in his own right. By 1270, he was responsible for the construction of many of the castles built at the behest of Philip I, Count of Savoy in the Viennois commune.

This association with royalty is, assumedly, how he made the transition from mainland Europe to the court of Edward––the earliest references in the English records of James date to 1278, where he is described as ‘going to Wales to put in order the works of the castles’.

He was appointed Master of the Royal Works in Wales around 1285, giving him full control of the construction of all fortresses, including Caernarfon Castle, Conwy Castle, Harlech Castle and of course Beaumaris. Noticeably, the design of all of these buildings share a unique and mostly uniformed style––one that features a heavy, Savoy-Norman French influence. Flourishes aside, nearly all of the Welsh castles and town walls built by him have survived battle, age and weather of 800+ years, mostly intact.

Beaumaris Castle was the last Welsh castle built by James, who died in 1309 before its intended completion date.

Beaumaris Castle construction

Work officially began on Beaumaris Castle in 1295, although initial plans had likely been first conceived closer to the start date of the invasion (est. 1284). This delay has long been attributed to a lack of funds, much of which was also being allocated to the king’s simultaneous invasion of Scotland.

Together, James St. George and Edward eventually plotted an ideal space along the Menai Strait––which would be able to facilitate restocking by sea during wartime––which would become the island site for ‘beau mareys’, or ‘beautiful marsh’.

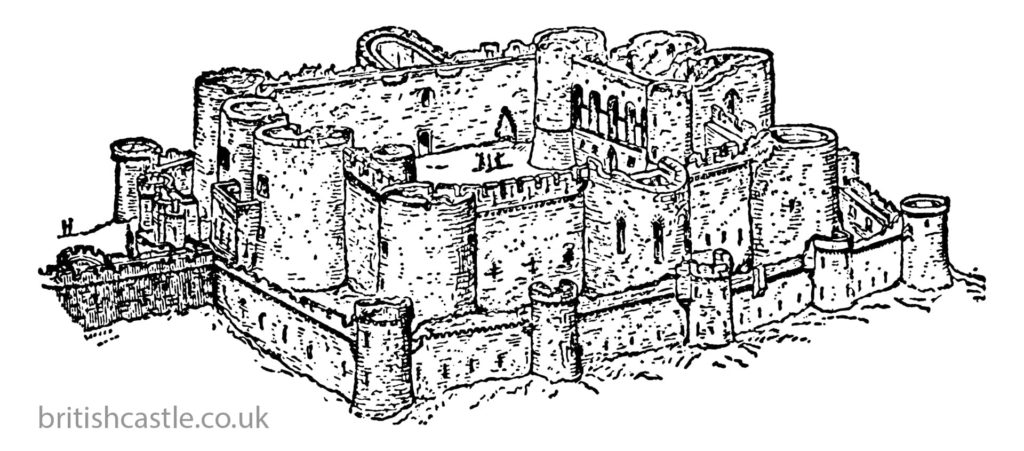

The result was a structure of immense size and presence: no fewer than four concentric rings of formidable defences included a water-filled moat with its very own dock. The outer walls alone bristled with 300 arrow loops.

Comprised of local stone, Beaumaris Castle features an outer ward flanked by two gatehouses and twelve towers. There is also an inner ward, overlooking the outer, that features another two large gatehouses and an additional six towers. Due to its proximity to the water, Beaumaris’ south gate could be reached by ship, while the inner wards were large enough to accommodate multiple families.

Beaumaris through the years

As impressive a steading as it was, construction on Beaumaris was not to last. Lack of money and trouble brewing in Scotland meant building work had petered out by the 1320s: the south gatehouse and the six great towers in the inner ward never reached their intended height; the Llanfaes gate was barely started before being abandoned; and, in all, £15,000 had been spent on the construction of the incomplete fortress––a massive sum for the time.

And despite its mighty features, Beaumaris Castle was not impenetrable. During the Glyndwr Rising, in which Welsh leader Owain Glyndwr attempted to lead a war for independence from the English in 1403, Beaumaris was taken by forces but eventually recaptured in 1405. Over the years, it suffered extensive wartime damage and decay, particularly after the English Civil War of 1642.

Although officially, Beaumaris Castle was never fully completed, the near-perfect symmetry of the fortress’s inner and outer structures makes it nothing short of an unfinished masterpiece. In 1986, Beaumaris Castle was classed as a World Heritage site by UNESCO; it is also considered a Grade I listed building by Historic England and Cadw––which currently manages the site, along with the other castles from Edward I’s reign.

Today, more than 700 years later, Wales’ Beaumaris Castle remains not only a popular tourist attraction, but also a long standing symbol of debate surrounding Welsh identity.